| Front page | | Bottom |

Denne rapport præsenterer resultatet af 2009-evalueringen på universitetsområdet, der blev gennemført fra december 2008 til november 2009 af et uafhængigt internationalt evalueringspanel.

2. THE EVALUATION – BACKGROUND, PURPOSE AND PROCEDURE

Colophon

Download the publication as PDF [512 kB]

Universitets- og Bygningsstyrelsen

Bredgade 43

1260 København K

Tlf: 3395 1200

Fax: 3395 1300

ubst@ubst.dk

http://www.ubst.dk

Denne rapport præsenterer resultatet af 2009-evalueringen på universitetsområdet, der blev gennemført fra december 2008 til november 2009 af et uafhængigt internationalt evalueringspanel. Evalueringen blev igangsat på baggrund af Folketingets beslutning V9 af 16. november 2006 og gennemført i overensstemmelse med Kommissorium for evaluering på universitetsområdet af 2. december 2008.

Efter introduktionen følger evalueringspanelets overordnede konklusioner i kapitel 1. Kapitel 2 præsenterer baggrunden, formålet og proceduren for evalueringen.

I kapitel 3 beskriver panelet den globale, europæiske, nordiske og danske sammenhæng, som den danske universitetssektor indgår i. Kontekstbeskrivelsen leder til en kort gennemgang af de forhold, som sammen med de formelle rammer har dannet en referenceramme for panelets evaluering.

Kapitel 4 og 5 præsenterer panelets vurderinger og anbefalinger, struktureret i overensstemmelse med den referenceramme, der er beskrevet i kapitel 3.

Der er vedhæftet en række bilag til rapporten inklusive en kort faktuel beskrivelse af den danske universitetssektor i de senere år.

Den danske universitetssektor har gennemgået væsentlige ændringer og reformer i løbet af de senere år i tråd med internationale reformtendenser på området. Panelet har brugt intentionerne bag de største reformer, universitetsloven af 2003 og sammenlægningsprocessen i 2007, som referenceramme for dets vurderinger og anbefalinger. Begge reformer har til hensigt at styrke universitetssektorens globale konkurrenceevne. Et yderligere referencepunkt er den danske Globaliseringsstrategi, der på linje med de globale tendenser er rettet mod at styrke videnstrukturen i samfundet. Globaliseringsstrategien fokuserer blandt andet på at øge andelen af unge, der gennemfører en videregående uddannelse, etablere flere ph d -stipendier, fremme internationaliseringen af de videregående uddannelser samt forbedre relationen mellem universiteterne og den private sektor for så vidt angår innovation. For at opnå de ønskede resultater af de forskellige reformer har Folketinget forøget de offentlige midler til forskning væsentligt.

Universiteterne har opnået større autonomi, og deres beslutningskapacitet er blevet forbedret. Imidlertid er denne udvikling blevet ledsaget af omfattende og i mange tilfælde meget detaljeret regulering. En egentlig forøgelse af universiteternes overordnede ansvarsområder er derfor mindre tydelig sammenlignet med centraladministrationens ansvarsområder. Det er legitimt, at universiteterne skal stå til ansvar for anvendelsen af de omfattende offentlige midler, som bliver investeret i dem. Men nogle af de nuværende regler hæmmer autonomien, medfører unødvendig administration og besværliggør universiteternes strategiske udvikling. Det nuværende sammenflettede ansvar gør de forventede effekter af styrket universitetsautonomi mindre tydelige, især på specifikke områder inden for uddannelse og ledelsesstruktur. Samtidig har universiteterne ikke fuldt ud implementeret deres opgaver og forpligtelser som ansvarlige, autonome institutioner. For at imødegå disse modsætninger anbefaler panelet en ”højtillids-strategi”: politikerne og de udførende myndigheder bør fastsætte de overordnede strategiske målsætninger og lade universiteterne selv fastlægge, hvordan disse målsætninger opnås. En sådan fordeling af ansvar er i overensstemmelse med intentionerne bag universitetsloven af 2003.

Medbestemmelse for medarbejdere og studerende er behandlet i universitetslovens bestemmelser om de interne ledelsesstrukturer, herunder universitetsbestyrelse, akademisk råd, studienævn og ph d -udvalg. Desuden fastlægger bemærkningerne til universitetsloven, at dekaner og institutledere er forpligtet til at sikre inddragelse af medarbejdere og studerende. Men hverken loven eller bemærkningerne indeholder en generel bestemmelse til sikring af medbestemmelse, og universiteterne har ikke indført medbestemmelse i tilstrækkelig grad. For at yde retfærdighed til de danske demokratiske traditioner og universitetslovens ånd for så vidt angår involvering af medarbejdere og studerende i relevante beslutningsprocesser, og samtidig gøre dette til et almengyldigt ansvar for universiteterne, anbefaler panelet, at der i universitetsloven eller bemærkningerne til loven indsættes en generel bestemmelse, som præciserer den individuelle universitetsbestyrelses forpligtelse til at sikre en tilfredsstillende praksis for medbestemmelse. En sådan bestemmelse bør også sikre, at universitetsbestyrelserne indfører procedurer for høj grad af gennemsigtighed ved udpegning af universitetsledere og eksterne medlemmer af universitetsbestyrelserne.

I Danmark lægges der stor vægt på såvel forskningsfrihed som den frie akademiske debat. En del af universitetsloven, nemlig paragraf 17 stk. 2, sender imidlertid et mindre hensigtsmæssigt signal, idet den kan opfattes som en indgriben i universitetsforskeres traditionelle værdier og rettigheder. Panelet anbefaler Folketinget at fjerne eller omformulere paragraf 17 stk. 2. For eksempel kunne stykket ændres til at fastsætte, at forskningsfriheden skal være garanteret inden for de rammer for videnskabelig kvalitet, såvel som de institutionelle og finansielle rammer, som den enkelte forsker arbejder inden for.

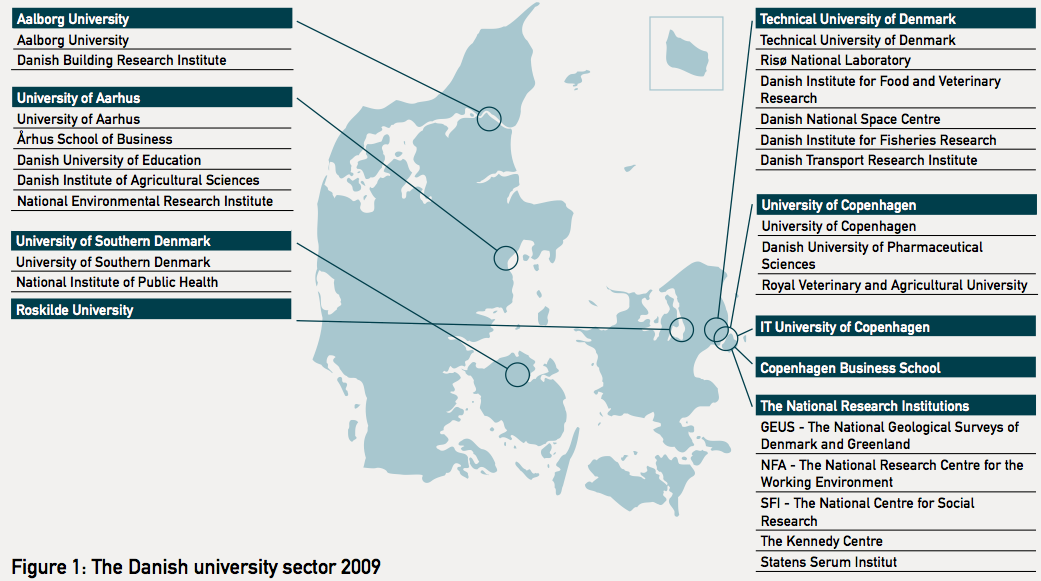

Sammenlægningerne mellem universiteter og mellem universiteter og sektorforskningsinstitutioner er blevet gennemført for at styrke universitets- og forskningssektoren, specielt set i et internationalt perspektiv. Sammenlægningsprocesserne har virket som igangsættere af forandring på flere måder. Der er opnået visse positive effekter, men den fulde virkning er endnu ikke opnået, især på grund af den korte periode siden sammenlægningerne. Ikke desto mindre forventer panelet, at universiteterne med tiden vil opfylde det potentiale, som sammenlægningerne har medført. Panelet anbefaler, at det diskuteres, om det nye ’landkort for universiteter og forskning’ tjener det danske samfunds interesser i tilstrækkelig grad, og at yderligere justeringer af ’landskabet’ overvejes. Spørgsmålet om universiteternes profiler var ikke et nøglespørgsmål på sammenlægningstidspunktet, men nu er tiden moden til at drøfte profilering. Panelet anbefaler en debat rettet mod at fastlægge, hvilken diversitet der ønskes i den danske universitetssektor. Drøftelserne kan specificeremålene vedrørende forskningsresultater og deres effekt, for sektoren som helhed såvel som for hvert enkelt universitet.

Med hensyn til Det Nationale Fødevareforum konkluderer panelet, at Fødevareforummet i dets nuværende form ikke fungerer tilstrækkelig effektivt. Hvis Danmark ønsker en ledende rolle inden for landbrug og fødevareindustri, kunne der formuleres en national ’fødevarestrategi’, som kan påvirke og stimulere de involverede universiteter såvel som samspillet mellem landbruget, fødevareindustrien og universiteterne.

This report presents the outcome of the Danish University Evaluation, carried out December 2008 – November 2009 by an independent international evaluation panel. The evaluation was initiated on the basis of the Danish Parliament resolution V9 of 16 November 2006 and carried through in accordance with the Terms of Reference for the 2009 Danish University evaluation of 3 December 2008.

After the introduction, a summary of the Evaluation Panel’s overall conclusions is provided. Chapter 2 presents the background, purpose and procedure of the evaluation.

In chapter 3 the Panel describes the Global, European, Nordic, and Danish context of which the Danish university sector is part. The context presentation leads to a brief description of the perspectives and framework, according to which we have structured our evaluation while at the same time taking basis in the formal framework for the evaluation.

Chapters 4 and 5 present the Panel’s assessments and recommendations. These are structured in correspondence with the framework described in chapter 3.

Several annexes are attached to the report, including a brief presentation of facts and later years’ history of the Danish university sector.

In line with international reform trends in higher education, the Danish university sector has undergone substantial changes and reforms during the last years. The Panel has taken the intentions behind the main reforms, i e. the 2003 University Act and the 2007 merger processes, as a frame of reference for its assessments and recommendations. Both are aimed at further strengthening the university sector’s global competitiveness. Another reference point is the Danish Globalisation Strategy, which follows the global trends and the increasing demands in supporting the knowledge structure in society. The Globalisation Strategy, among other things, focuses on increased access to higher education, creating more PhD positions, stimulating a further intensification of the in ternationalisation of higher education as well as a more effective innovation relationship between universities and the private sector. For achieving the intended outcomes of the different reforms, the Danish Parliament has substantially increased the public funding of research.

More autonomy of the universities has been achieved and the decision-making capacity of universities has been improved. However, this development has been accompanied by a dense set of rules and regulations, many of them too detailed. An actual increase in the overall responsibilities of the university level has therefore been less evident, compared to the responsibilities of the central administration. Accountability is legitimate – the universities must account for the substantial public funding invested in them. Some of the present rules and regulations, however, are hampering autonomy, entailing unnecessary administration and interfering with strategic university processes. The present intertwined responsibility, especially with respect to certain education issues and specific features of the leadership structure, makes the expected effects of the strengthened university autonomy less obvious. At the same time the universities have not fully materialised their tasks and responsibilities as accountable autonomous institutions. To address the underlying contradictions the Panel recommends a high-trust strategy: the politicians and the implementing authorities should be expected to stick to overall strategic targets and leave to the universities to decide how to reach the targets. Such a division of responsibilities is in line with the intentions behind the 2003 University Act.

The codetermination for staff and students is covered by the University Act’s stipulations with respect to the internal governance structures, above all the university boards, the academic councils, the study boards and the PhD-committees. In addition the explanatory notes to the Draft Bill on Universities stipulate obligations of Deans and Heads of Department to ensure involvement of staff and students. However, neither the Act nor the explanatory notes contain a general statement in support of codetermination, and the universities have not implemented codetermination to a satisfactory extent. In order to do justice to Danish democratic traditions and the spirit of the Act as regards academic staff and students’ involvement in relevant decision-making processes and at the same time making this a general responsibility for the universities, the Panel recommends that a general statement stipulating the individual university board’s obligation to secure adequate codetermination practices should be included in the Act or in the explanatory notes. Such an amendment should also ensure the university boards to be active in the implementation of procedures for a high degree of transparency in nominating senior executives as well as the external members of central university boards.

Regarding the freedom of research as well as the freedom of debate, the intentions and expectations in Denmark are high. One part of the University Act, though, sends a less expedient signal, namely the article 17 2, which could be regarded as an intrusion into traditional values and rights of academic university staff. The Panel recommends the Parliament to remove or reformulate article 17 2. An example of change of the Act could be to let the article stipulate that research freedom should be guaranteed within the specific financial and quality framework of the institution of the researcher.

The mergers between universities and between universities and government research institutions (GRIs) have been carried through in order to strengthen the university and research sector, especially in an international setting. The merger processes have in certain ways acted as change drivers. The effects of the mergers have not yet been fully materialised, even though there are certain positive effects, and the short time since the merger decisions have not allowed for a more comprehensive implementation. Nonetheless, the Panel expects the universities to fulfil in due time the potential of the mergers. In order to be more competitive, the Panel recommends the adequacy of this new ‘map of universities and research’ to be discussed for serving the interests of the Danish society and economy, and the ‘landscape’ to be adjusted with further mergers and other adjustments. As the question of university profiles did not exist as a key issue for the mergers at the time of the merger process, it might now be time for discussing the profiling of the universities. The Panel therefore recommends a debate on university system diversity, aimed at determining what kind of diversity basis the system should have. The discussion may include possible targets for the university system as well as for each individual university when it comes to research output and impact.

Concerning the Danish Food Forum, the Panel concludes that the Food Forum in its current set up is not functioning effectively. Assuming that Denmark wants a leading role in agricultural and food industry, a framework for a national ‘Food Strategy’ might be set up, to influence and stimulate the universities concerned as well as the interaction between the food/agricultural industry and the universities.

This chapter presents the background for and purpose of the 2009 University Evaluation, including a brief presentation of the evaluation procedure and the Evaluation Panel. This initial presentation of the “setup” for the evaluation is followed in chapter 3 by the perspectives and framework based on which the Panel has structured its assessments, including the Panel’s description of the wider context the Danish university sector is part of.

The 2009 University Evaluation has been initiated on the basis of the Danish Parliament resolution V9 of 16 November 2006, and carried through in accordance with the Terms of Reference for the 2009 Danish University evaluation of 3 December 2008.

As indicated in the Terms of Reference (annex 1), The Danish Parliament’s resolution V9 (Denmark’s Liberal Party, The Conservative People’s Party, and The Danish Social Democrats) of 16 November 2006 sets out the formal framework for the evaluation:

“The Danish Parliament accepts the answer from the Minister of Science, in that it:

> Notes that the purpose of the mergers are more education, greater international impact of research, more innovation and collaboration with industry, the attraction of more research funding from the EU, as well as a continued competent service in the area of government commissioned research.

> Notes that the institutions’ self-determination has been the core principle in the mergers of the universities and the government research institutions, which are to come into effect on January 1, 2007.

> Underlines the importance of the university law’s provisions concerning research freedom and employees’ freedom to participate in the public debate.

> Notes that the Minister of Science in 2009 will conduct an evaluation of the extent to which the purpose of the university mergers has been achieved.

> Notes that the Minister of Science in 2009 furthermore will conduct an evaluation of the state of codetermination for employees and students at the universities, the free academic debate, and research freedom, under the current university law ”.

The purpose of the evaluation has been to investigate the issues described in the Danish.

Parliament’s resolution V9, as well as issues concerning the development of degrees of freedom (autonomy) for the universities, with the main focus on the effect of the reform of 2003 (the 2003 University Act) and the 2007 reform (the mergers of universities and government research institutions). According to the Terms of Reference, “The aim of the two reforms was to provide universities with an enhanced capacity for strategic prioritisation across their core areas of activity: education, research, and knowledge transfer, as well as with an enhanced ability to meet demands of society ”.

In connection with the purpose of the evaluation, the Terms of Reference specified that: “The creation, through the reform of 2003, of a clear and transparent management structure including appointed leaders and governing boards with a majority of members from outside the university, forms the basis for the evaluation ”.

With reference to the explanatory notes for “The Draft Bill to Changing the University Act (L140) of 31 January 2007”, the Terms of Reference stipulated that the evaluation should be conducted independently.

The document “Proposal for minimum contents of the 2009 evaluation of 18 November 2008”, including amendments of 29 January 2009 (annex 2) also belongs to the formal framework for the evaluation. It comprises the following evaluation areas:

A. Fulfilment of the purpose of university mergers

1. More education

2. Greater international impact of research

3. More innovation and collaboration with industry

4. Attraction of more EU-funding

5. Continued competence in commissioned services to government.

B. Codetermination for employees and students

C. The free academic debate

D. Research freedom

E. Degrees of freedom (Autonomy).

The Panel notes that the data available this early after the completion of the mergers will not be sufficient to establish valid causal links. Regarding the mergers the Panel therefore has had to rely to a large extent on experiences, perceptions, and interpretations.

The main objects for the evaluation were the eight Danish universities, i e. the five universities that have undergone mergers in 2007 (University of Copenhagen (KU), Aarhus University (AU), Technical University of Denmark (DTU), University of Southern Denmark (SDU) and Aalborg University (AAU)), and the three universities that did not merge (Copenhagen Business School (CBS), Roskilde University (RUC), and IT-University of Copenhagen (ITU)). In addition, the following four government research institutions, which were not merged, have been included in the evaluation: SFI - Danish National Research Centre for Social Research; NFA - National Research Centre for the Working Environment; GEUS - Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland; and: The Kennedy Centre. Finally, DFF – Danish Food Forum (“Det Nationale Fødevareforum”) has been included in the evaluation. The inclusion of the latter in the evaluation was decided in connection with the foundation of DFF, which took place as a consequence of the mergers.

The evaluation has drawn upon a number of surveys and analyses conducted by private consultants, and statistical data delivered by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation and the Danish University and Property Agency. The evaluation has also benefited from comprehensive written reports and statements from the individual universities as well as from Universities Denmark, the non-merged government research institutions, relevant Ministries and several other stakeholders. Furthermore, the Panel has included the recent evaluations of SFI and NFA as the basis for its investigations in relation to these two institutions. An overview of the background material is enclosed as annex 4.

In addition, the Panel has based its evaluation on information and opinions obtained from meetings with employees, students, and management representatives of the individual universities, as well as with representatives of non-merged government research institutions, relevant ministries and relevant stakeholders and collaboration partners of the universities. The meetings with the universities and other stakeholders took place during the Panel’s nine days assembly in Denmark 20-28 August 2009. In addition, ahead of the August assembly, on 12 May 2009, the Panel Chair and one Panel Member met with a number of stakeholders. Programmes for the Panel’s meetings with the universities and other stakeholders are enclosed in the time and work plan for the evaluation (annex 6).

The meetings were held as informal discussions on the basis of specific questions prepared in advance, aimed in particular at gaining information and viewpoints supplementary to the received background documents, focusing especially on the impact of the mergers and the university sector policy instruments (legislative, financial and dialogue based instruments).

The Panel has had several internal meetings for planning as well as for discussing its observations, assessments and recommendations (see annex 6). From August to November 2009 the Panel completed the evaluation report. The Panel’s communication on the report took place via e-mail, telephone and meetings.

In accordance with the Terms of Reference, the evaluation has been conducted by an external, internationally composed evaluation panel. Annex 3 provides a brief description of the Panel which consisted of the following experts:

> Dr. Agneta Bladh, Rector, University of Kalmar (chair)

> Professor Elaine El-Khawas, George Washington University

> Dr. Abrar Hasan, Independent Consultant

> Professor Peter Maassen, University of Oslo

> Professor Georg Winckler, Rector, University of Vienna

Pia Jørnø, M.Sc. , independent consultant and science writer, served as academic secretary for the Panel. Søren Poul Nielsen, M.A., independent consultant, served as additional academic secretary during the Panel’s meetings with universities and stakeholders in August. Both served independently of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation

The reform forces and expectations that confront universities around the world also apply to the Danish universities. Danish universities and this evaluation must take account of these contextual forces for better understanding the challenges Danish universities are facing nationally and internationally. There are, firstly, the global reform trends. With Denmark’s goal of developing a world class university system that can support the global competitiveness of the country’s economy, it joins a large number of other countries with similar ambitions. Countries around the world are introducing reforms aimed at creating conditions under which their universities can compete with the best universities in the world. Secondly the European context is of particular significance for Danish universities from the perspective of the development of the European Higher Education Area (as part of the Bologna Process) as well as the European Research Area. In the framework of this evaluation, especially the role of the European research funding is examined. Thirdly in the Nordic context the interconnections are strong. In this context especially common Nordic political and cultural values and traditions are of relevance. Finally, university reforms within the country take place within the context of wider socio-economic and political forces. University reforms in Denmark have been shaped by and must take account of such developments as the Government’s Globalisation strategy. These four elements are discussed below as a prelude to describing the Panel’s evaluation perspective, which is taken up at the end of the chapter.

Two global trends: Strengthened autonomy and strengthened regulatory regimes

Faced with these changes governments in all OECD countries are engaged in reforming their higher education system. In this, special attention is given to the governance modes with respect to higher education. This concerns both the system level governance approach and the intra-institutional governance structures. There are two clear and opposite directions of change. One, in continental European countries, and the Asian OECD countries, where levels of university autonomy were traditionally low, there is a move to expand the degree of institutional autonomy. The second orientation, visible in those countries in which universities enjoyed traditionally high degrees of autonomy, is to strengthen the regulatory regime to bring the more autonomous university sectors more in line with the requirements of the public interest.

These opposite, but complementary, trends represent the need for national governments to find an appropriate balance between system level order and the need for governmental control versus an effective level of system diversity and autonomy of the public sector institutions including universities (Olsen 2007). The two trends represent attempts to improve the governance balance between government and higher education: either through strengthening university autonomy or to reduce university autonomy in certain areas from a public interest perspective. This also implies that university autonomy is not an aim in itself, nor can be absolute. It is part of a complex governance relationship that has to be reviewed and adapted regularly in order to assure its continuous effectiveness.

Consequently, the key question governments are struggling with, when it comes to governing their university systems effectively, is the following:

How to provide appropriate levels of institutional autonomy and, at the same time, complement institutional autonomy with an accountability regime that satisfies the public interest without becoming a constraint on universities’ responsiveness and innovation?

Since the second half of the 1990s there has been a growing political focus in Europe on the possible consequences of globalisation. This development was ignited by the perceived weaknesses of the European economies in comparison to the US economy and the rapid rise of China and India as important economic powers. The heads of state of the EU members have expressed their worries and presented their strategies for addressing the challenges for Europe in the so-called Lisbon 2000 Agenda, which aims at strengthening the economic competitiveness of Europe as well as improving the social cohesion of its societies.

As a consequence, there is at the beginning of the 21st century a clear political “momentum” for the university in Europe. The Lisbon Summit of 2000 has (re-)confirmed the role of the university as a central institution in the “Europe of Knowledge”. Consequently, we can observe that since 2000 the Commission has become highly interested in the university as an object of European level policy-making. This is clearly inspired by the interpretation of the university’s central role in connecting education, research, and innovation (the Knowledge Triangle), and the assumption that the effectiveness of this connection is considered to be of major importance for the competitiveness of Europe’s economies and the level of social cohesion of its societies. In the Commission’s communications and other policy papers the university has either directly or indirectly become a central concern.

The general worry about “global competitiveness” is primarily focused upon the European research-intensive university. Based on indicators and statistics, especially international rankings, but also on statistics such as the number of international students in Europe, the number of European students in Australia and the US, and the number of European academics at US universities, the view dominates that the European University is lagging behind. Reform is promoted as the means through which European universities can compete (again) with their US counterparts.

The European level reform proposals use two organisational models as their main frame of reference, namely the leading US research universities and the successful enterprise and its assumed style of organisation and governance. The first defines the crisis of the European university and is organised around the question: “Why is there no Euro-Ivy League?” (Science 2004: 951) The second presents the solution: European universities have to become more like private enterprises operating in competitive environments.

The university reform agendas that are presented at the European level focus especially on the relationship between research and innovation. The legitimacy of the European Commission to launch university reform ideas is based on its competence in the area of research policy, which has been developed since the beginning of the 1980s. The most important research policy instrument for the Commission has been the multi-annually framework programmes (FPs). The first FPs had a purely economic rationale, but they gradually expanded in disciplinary scope and funding. The attached objectives became more heterogeneous covering not only economic but also ecological, social, and political rationales.

The Lisbon 2000 summit led to important innovations in the aims, organisation, and ambitions of the FPs, as well as to the introduction of the European Research Area (ERA). Through the ERA the EU intends to influence and integrate the national research policies of its member states. The ERA ambitions are, amongst other things, expressed in the joint 3 % target of GDP to be invested in research and development. In addition, in the development of the latest FP (FP7), the member states and the EU agreed upon the establishment of the European Research Council (ERC) which is a considerable institutional innovation at the European level. It is significant because it entails changing the idea and principles of research funding in Europe. To understand the innovative nature of the ERC, the following transformative dimensions are of relevance:

> The ERC brings basic research into the heart of the EU research policy, i e. as a separate construction within the Seventh Framework Programme (FP7).

> The establishment of the ERC changed the definition of what kind of research is a legitimate concern at the EU level.

> The ERC represents a break with the established principles of criteria for European research funding with the “excellence only” principle, no pre-determined research topics and no criteria of trans-nationality or even research collaboration, but highly selective funding given to individual researchers and their teams.

Currently, the EU research funding context for Danish universities consists first and foremost of the FP7, one of the largest public research programmes in human history with a budget of over € 50 billion to be distributed in the period 2007-2013. The underlying assumption for the FP7 is that it will be a major step towards creating a world class European research environment through stimulating competition for research funding among Europe’s best and most ambitious researchers; stimulating mobility of the best researchers leading to strategic concentrations of top researchers in a limited number of European universities, public non-university research institutions, and the private sector; and stimulating national research councils, ministries and university leadership to develop strategic priorities in line with the research agendas of the European Commission.

While (higher) education has traditionally been a nationally sensitive policy area in the EU, also here the Lisbon Summit marks an important beginning of more direct involvement of the European Commission in educational policies. The Erasmus Mundus programme has, for example, given a major boost to the development of international joint degree programmes in Europe.

Finally, we wish to mention the Bologna Process. Currently 46 European states participate in this intergovernmental process, documented by the communiqués of the bi-annual ministerial conferences. The Bologna Process aims at creating the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) characterised by a compatibility and comparability of national higher education systems based on a three cycle structure. As stressed in the Leuven communiqué of April 2009, the Bologna Process is “firmly embedded in the European values of institutional autonomy, academic freedom, and social equity” and requires “full participation of students and staff”. Intra-European mobility of students, early stage researchers, and staff, is one of the main concerns of the Bologna Process. The Leuven communiqué states the ambitious goal that, by 2020, “at least 20 % of those graduating in the countries of the European Higher Education Area should have had a study or training period abroad” Although, officially, the Bologna Process is a purely intergovernmental process among nearly all European states, it is more and more driven by various stakeholders including the European Commission, the latter successfully trying to integrate EU’s education and lifelong learning policies and programs with the Bologna agenda.

The Danish universities are positioned in a number of international arenas, including the Nordic region consisting of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and the autonomous territories of Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and Åland. Nordic cooperation within higher education was established well before the current focus on the economic and societal impact of universities. While the traditional rationale for Nordic cooperation within higher education was culturally and academically based, such traditions are challenged by emerging new rationales for universities’ internationalisation and relations to economy and market competition. Nonetheless, for understanding the Danish university dynamics, the Panel finds it of relevance to reflect briefly on the main dimensions of Nordic higher education.

Similar to the EU with its Lisbon Agenda, in 2000 the Nordic Council of Ministers also adopted a Nordic Agenda and a strategy for Nordic cooperation. The Nordic Agenda highlights five areas of special importance for Nordic cooperation:

> Technological development with special reference to the information society and Nordic research

> Social security and the possibility for Nordic citizens to live, work, and study in another Nordic country

> The internal Nordic market and cooperation for abolishing border obstacles > Cooperation with neighbouring countries and neighbouring regions > The environment and sustainable development in energy, transport, forestry, fishery, and trade and industry.

In 2005, this Agenda was followed by a joint strategy of the Nordic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers as presented in the report “Norden som global vinderregion” [The Nordic Region as a Global Winner region]. The report argues that the Nordic region is under pressure from globalisation and increased international competition from China and India, and that this raises the question of what the Nordic region should base its economy and welfare in the future.

As a consequence of the agreements reached in the Nordic Council and Nordic Council of Ministers over many years, the Nordic countries have developed a common labour market, have established common institutions in various policy areas, and have developed cooperation schemes and programmes. With respect to education this has resulted in various mobility programmes for pupils, students, teachers, and researchers (including the Nordplus programme for students and teachers); agreements for the mutual recognition of degrees and study programmes, simplified admission requirements for Nordic students throughout the region; and various expert committees for policy issues and cooperation initiatives. Further, a number of cooperation programmes have been implemented relating to research. The Nordic Science Policy council was established in 1983, and cooperation in the area of research training has existed since 1990.

The socio-economic, political, and cultural similarities between the Nordic countries form a solid foundation for their long-term cooperation, and form at the same time a good basis for a continuing bench-marking in different areas, including education and research. Although there are clear political, economic, and historical differences between the countries, policy-making in this region is often characterised as being a result of the “Nordic Model”. With respect to higher education, typical ingredients of this model are public higher education institutions with institutional autonomy in many areas, a democratic intra-university governance structure with a structured involvement of staff and students, high levels of state investments, strong emphasis on equality concerning the institutional landscape and the way in which public resources are allocated throughout the system. To complement this picture, the Nordic states have traditionally also offered quite favourable student support schemes with the aim of stimulating high participation rates in the sector.

Denmark is one of the European countries that have developed a specific national globalisation strategy called “Progress, Innovation and Cohesion Strategy for Denmark in the Global Economy”. Responsible for this strategy was a Globalisation Council set up in 2005 and consisting of representatives of many sections of society. The strategy can be re-garded as one of the most straightforward and explicit national level initiatives in Europe to handle the challenges of the global economy. In the analysis underlying the strategy a number of the Danish strengths and weaknesses have been highlighted. The strengths indicated are the strong national economy, the flexible labour market, low unemployment and a highly educated population. The indicated main weaknesses are the ageing population, the high cost and price level of the Danish economy, and the fact that the Danish education system is not geared towards a knowledge society. The latter expresses itself in the following characteristics: Danish students begin and complete their studies late (age wise), higher education programmes have a high drop out rate, and the number of graduates in natural and engineering sciences is too low.

The Globalisation Strategy has, as such, a strong focus on education and research on the basis of the starting point that “Human knowledge, ideas and work effort are key for exploiting the opportunities of the globalisation” (In Danish: “Menneskers viden, idérigdom og arbejdsindsats er nøglen til at bruge de muligheder, som globaliseringen giver os”). In its implementation, this focus has even become more pronounced, implying that the globalisation strategy has become, in the first place, an education and research policy strategy.

The most important university-oriented policy goals introduced in the framework of the globalisation strategy are to:

> raise the public investments in research from 0 75% to 1% of the Danish GDP; > link the basic public funding of universities more directly to the quality of their activities;

> integrate the government research institutions (GRIs) into the universities;

> double the number of PhD students;

> introduce a system of accreditation for all university education programmes;

> increase the higher education participation rate from 45 to 50%;

> stimulate a more rapid throughput of higher education students;

> introduce better and more structured options for Danish students for studying abroad.

To realise these policy goals a number of specific measures and reforms have been intro-duced in the Danish university sector, including the university merger processes. These are not isolated, but relate to the Danish political system’s overall reform efforts with respect to higher education, which include the 2003 University Act aiming at university autonomy. All these efforts are aimed at further strengthening the Danish universities and, as one of the underlying goals, enabling the universities to compete in a number of fields with the world’s best universities. The Danish Globalisation Strategy, also mirroring the trends in Europe, as well as other parts of the world, is thus an important component of the basis for this evaluation

As indicated, the changes and expectations that confront universities around the world also apply to the Danish universities. As expressed in parliamentary resolution V9, the overall aim of the two main university reforms introduced by the Danish Government in the 2000s was to create the conditions under which the universities would be able to develop their own strategic priorities with respect to their education, research, and innovation tasks. In addition, the reforms were intended to improve the relationships between the universities and society.

The first of these two reforms, i e. the 2003 University Act, was focused on establishing university autonomy while at the same time ensuring accountability. The new Act introduced a major change by modernising the intra-university governance structure through moving decision making responsibilities from collegial, representative councils to appointed leaders (rector, deans, and heads of department). Further, the new Act aimed at improving the relationship between universities and society through the introduction of central university boards with a majority of external members. This reform was followed by the 2007 merger operations that led to fewer universities and a concentration of publicly funded R&D in the university sector.

The university merger processes consisted of an integration of GRIs into the university sector, which was a target of the globalisation strategy; and mergers between universities, which was initiated by the Government. The integration of GRIs had as its main aims to stimulate research synergies between until now institutionally separated sectors; to fertilise the university sector with practice oriented research leading to close contacts with societal, i e. private and public sector agencies; and: to make additional research resources available for educational processes, leading to a strengthening of the link between higher education and research.

As such, the 2003 Act can be seen as creating the governance conditions for the profiling and strategic prioritising of universities, while the merger processes added a substantive dimension through the concentration of research capacities in selected areas in specific universities. The Panel’s evaluation framework is based on the nature and aims of these two reforms.

Consequently, the Panel has organised its evaluation and assessments along two lines, i.e. first developments with respect to university governance since 2003 (focusing on two sub-lines: university autonomy, and codetermination and academic freedom); and second the effects of the mergers on the dynamics and productivity of the university system

The 2003 Act is in line with global reform trends aimed at modernising university management. Such reforms are not implemented in a vacuum, since the governance structures to be changed have their own traditions and characteristics that continue to have an influence long after the legal foundations for the structures have been altered. In the Danish case this means, for example, that the democratic traditions with respect to university governance, including the structured involvement of staff and students in intra-university decision-making, continue to have an influence also after the 2003 reform. As such the introduction of appointed leaders in university governance structures, and the establishment of central executive boards, have ameliorated the formal decision-making capabilities of the universities, but the demand for a democratic intra-university governance structure has also continued. As a consequence, for it to be successful and effective, the 2003 reform needs to lead to an appropriate balance in the intra-university governance structure between top-down oriented executive leadership, and a bottom-up management style, which should include an effective involvement of staff and students in academic decision making at all appropriate levels.

In addition, the framework conditions, within which the university leadership can operate autonomously, demand an “arm’s length distance” from the side of the involved Ministries and the Parliament, which implies the setting of overall targets, instead of an interference through detailed regulations and control in the day-to-day responsibilities of the university management. One of the conditions for this is a high level of trust from the central authorities in the capabilities of the universities to use the autonomy in the expected way. In other words, an adequate balance between autonomy and accountability of the universities should be maintained. On the one hand, the universities, in order to keep up a high, or even world-class standard, need room to operate and develop. On the other hand the authorities, representing the tax payers, have a legitimate right to demand documentation for the universities’ prudent use of the substantial public funding.

Furthermore, academic freedom, including freedom of research and free academic debate, is a fundamental principle of university life, and both governments and universities must ensure respect for this fundamental requirement. To meet the needs of the world around a university, the research must be morally and intellectually independent, and it must be ensured that research issues can be freely selected, research methodology freely developed, and research results freely published in the framework of the employment conditions provided by the university and the assessments of peers from the same academic area.

While the 2003 reform created the governance framework for strategic leadership, the globalisation strategy provided the framework for making the next step, i e. creating the academic framework conditions for strategic prioritisation and profiling by stimulating merger processes that would lead to a concentration of research capacities in universities. The mergers were also expected to strengthen education, and especially upper level education degree programmes, amongst other things, by bringing research staff from the GRI sector into the universities. Mergers were also intended to create the conditions for effective relationships between universities and the private as well as the public sector, which would contribute to economically relevant, as well as other societal, innovations. The starting point for the merger process was the assumption in the Globalisation Strategy of the benefit in merging the government research institutions (GRIs) with the universities. Subsequently, the Government also initiated a merger process between universities. The stated expectations of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation were the establishment of a strongly reduced number of universities with ameliorated strength in the international setting.

Based on these perspectives, the Panel has in the first place studied and assessed the way in which specific governance aspects of the university sector have developed since 2003. In this, it has examined two specific issues:

> How have the 2003 Act, and regulations plus various other steering instruments following the Act, influenced university autonomy, and have the universities implemented the Act fully and adequately in the given conditions and framework?

> How has the implementation of the 2003 Act by the universities affected university democracy, more specifically the involvement of the staff and students in intra-university decision making processes; and the freedom of research and the free academic debate?

The issues of autonomy, staff and student involvement, research freedom and free academic debate are addressed in Chapter 4. In chapter 5 the Panel presents its assessment of the effects of the mergers, while recognising the methodological limitations imposed by the short period since the mergers. Mindful of this limitation, the Panel has attempted to analyse the effects of the mergers on the key issue of strategic positioning by universities in pursuit of the goal of strengthening the university sector’s global competitiveness.

> What kind of impact of the mergers can be seen so far on the main activity areas of the universities, i e. education, research, and innovation, on universities’ relationship with the private sector, and on government-oriented research?

In this chapter the Panel presents its assessments and recommendations as regards the. development of specific governance aspects of the Danish university sector since the introduction of the 2003 University Act and subsequent regulations. In line with the Panel’s Terms of Reference, we address two main aspects. Firstly, we assess the way in which the 2003 University Act, and regulations plus various other steering instruments following the Act, have affected university autonomy. In addition, we discuss the extent to which the universities have implemented the Act effectively in the sense of university autonomy. Secondly, we assess the effects of the 2003 University Act on intra-university governance issues and the universities’ implementation of the Act in the sense of intra-university governance. More specifically, we assess the involvement of staff and students in intra-university decision making processes, the freedom of research, and the free academic debate.

In line with international trends, the 2003 University Act changed the status of universities from being state institutions to autonomous bodies within the public sector. This changed the relative responsibilities of the universities and the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (henceforth referred to as the Ministry) in its oversight role over the universities. The overall task of the university board under the Act is to “safeguard the university’s interests as an educational and research institution and determine guidelines for its organisation, long term activities and development”. The Minister of Science, Technology and Innovation (henceforth the Minister) “is charged with formulating the framework for the universities’ activities; determining society’s requirements for the universities’ activities, and the size of the subsidies from the Danish state to support these activities; safeguarding the operational reality facing the university management and encouraging the management to make the sensible decisions from a socio-economic perspective” [E2, p 2].

For public institutions, such as the Danish universities, it is essential to ensure an adequate balance between autonomy and accountability. In order to maintain a high, or even world-class standard, the universities need room to operate and develop, while at the same time the tax payers have a legitimate right to oversee that the universities use the substantial public funding prudently.

The Panel finds that the 2003 Act provides for a high level of autonomy of the universities in appropriate balance with accountability. The Act itself does not constrain the universities from establishing a satisfactory level of autonomy and accountability – including the freedom to develop distinctive individual institutional profiles, while at the same time documenting for society how the public resources are spent on universities’ activities and achievements.

On basis of its interviews and the submissions it has received, the Panel also concludes that within the university sector and among various stakeholders there are widespread consensus that the Danish universities have gained greater autonomy through the 2003 Act. In general, universities appear to have become more dynamic because of the newly gained autonomy. The Act is generally welcomed and by and large, the stakeholders view the 2003 Act as a big step forward in strengthening the universities’ autonomous status and providing room for flexibility and innovation. The university leadership also welcomes the principle of dialogue initiated by the Minister following the 2003 Act, as well as the new auditing approaches that have been introduced.

Nonetheless, there remain a number of important constraints on university governance, and new ones have been added following the 2003 Act, many of which are in weak compliance with the intentions of the Act and are hampering the autonomy of the universities. The Panel mainly sees these problems within the following three areas:

> Regulations are often used as steering instruments for publicly funded institutions which are responsible for central societal tasks. At present, extensive rules interfere unnecessarily with the universities’ freedom to operate, particularly with respect to educational activities and the institutional management structure, including very detailed rules, overlapping rules, and rules which entail unnecessary administrative burdens and unclear division of responsibilities.

> Public funding is a powerful steering instrument, which can be used in a considerate manner to set incentives for achieving political goals, but can also be used in ways which impede the autonomy of the universities.

> A structured dialogue between the universities and the central administration is important in order to ensure an optimal balance between autonomy and accountability. However, the prerequisites given in the Act for the dialogue can impede university autonomy. At present, the restrictions given to the development contracts make them less appropriate as goal setting instruments.

In the following, the Panel will address the three above topics.

A number of Orders (regulations) have been implemented since 2003, both within and outside the framework of the 2003 Act, covering the areas of education and research [see full list in background document F5], and affecting university management. Some are decided by Parliament, some by Government, and some are decided at the ministerial level, by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation or other ministries. Furthermore, several regulations predate the 2003 Act but continue to operate.

It appears to the Panel that in the current national steering framework the universities’ activities are to be approved before implementation as well as controlled during operation, while also the output is monitored – via orders, accreditation criteria and procedures, supervisory bodies, development contracts, evaluations, etc. The Panel finds this to be an unnecessary duplication of control, which is not only hampering university autonomy but also wastes university resources that could be used more effectively.

Many of the external constraints are an intrusion into areas of competence, which should be the responsibility of the universities themselves. The constraints amount to a level, which may be called micro-management, and limit the university leadership’s room to manoeuvre and flexibility in its strategic decisionmaking and positioning. Some procedures, while not limiting university autonomy, are excessively bureaucratic and generate inefficiencies in university operations. Considerable administrative resources are demanded of the universities for reporting and applying for approval. This may very well impede the strategic and visionary management of the universities. This may arise due to a duplication of oversight, when more than one tool is used for the same purpose, or if the monitoring procedures employed are overly resource-consuming for the universities.

Regulations in the area of education are particularly limiting the universities’ autonomy, as they are wide-ranging, covering decision areas such as study programmes, admission, and enrolment procedures; awarding of parallel and joint degrees; and: arrangements for credit transfer, exams, grading scale, guidance and counselling, and quality assurance procedures.

Speeding up enrolment and graduation

As implied, the Panel has observed that several tools are used by the authorities and politicians to achieve the same goals. For example, in some cases, development contracts, taximeter rules, recruitment rules and rules on student counselling, are all geared, in part, to speed up enrolment and graduation. One unintended consequence is administrative inefficiency because responding to overlapping demands ties down resources of the universities and the commitment of such resources reduces universities’ room to manoeuvre in substantive areas.

Student intake and exams

Another example is that universities cannot decide on the criteria or procedure for student intake on their own. Student enrolment to bachelor’s programmes is controlled centrally through an Order (issued in 2008). The objective of the changes introduced in 2008 and 2009 was to expand enrolment in Quota 1 at the expense of Quota 2. Likewise, it was introduced that applicants applying no later than two years after having completed their upper secondary will have the average of their secondary school grades multiplied by 1 08 to raise eligibility.

The Government as well as the Parliament have passed specific decisions on matters that can be expected to lie in the competence of the universities, such as the abolishment of group exams, and the introduction of very detailed rules regarding re-examination within a short time after students’ failed passing of the “regular” exam. Also, detailed rules for students’ rights to complain are demanding excessive resources of the universities

Study programme accreditation process

The Panel is concerned that the current practice of regulations and procedures regarding the development of new or adaptation of existing study programmes can have negative effects. Quality control of study programmes is necessary, and it is important that universities function within an agreed national quality assurance framework. The difficulty with the current regulations is that in addition to regular external quality control of established study programmes, the Danish universities must obtain accreditation of new study programmes in advance from ACE Denmark (the accreditation institution for higher education). The requested resource commitments reduce the universities’ preparedness in responding rapidly to emerging demands for new skills and competences of master’s and bachelor’s programme graduates.

The Panel supports the general idea of the establishment of an independent institution under the Danish Accreditation Act. It provides an arm’s length approach to assuring the quality and relevance of the university study programmes, which replaced the previous system where the development of new study programmes was directly controlled by the Ministry on the basis of macro-efficiency concerns and criteria. In the new system, programme accreditation is based on an overall assessment of study programmes and a combined weighting of all the criteria of the Accreditation Order (such as demand in the labour market, research-based teaching, depth of education, results of the study programme). The Minister still determines the subsidy status, title, specific admission requirements for bachelor’s programmes, the prescribed study period, and any limit on student intake, before the Accreditation Council can approve a study programme. Through an amendment to the Act in 2007, universities are under obligation, as of January 2008, to set up recruitment panels for study programmes involving industry representatives.

There is universal complaint among the universities against the resource costs and inefficiency of the in-advance accreditation process. The Panel finds the lengthy process from an idea for a new programme to the actual start of the programme as hampering universities’ quick response to changing socio-economic knowledge, skills, and competences needs. From that perspective, it would be preferable to use also in Denmark the internationally dominant ex-post evaluation procedure instead of the current ex-ante accreditation practice.

Joint degrees, international collaboration on study programmes

In terms of the increasing internationalisation of education, the Danish regulations appear inflexible and are impeding the development towards an increase of Danish students going abroad for a shorter or longer period. For example, the cases of parallel and joint degrees are handled by a separate Order that lays down conditions for approval. These regulations take little account of the international environment in which Danish universities are operating. Furthermore, Danish regulations limit the international marketing of Danish study programmes, the establishment of joint degrees, and Danish universities’ participation in the Erasmus Mundus programme. For the latter, there has been a retrograde step in that initially the retention of the taximeter scheme for Erasmus Mundus students was achieved, but has subsequently been discarded (as of March 2009).

Top positions

While several areas of decision making regarding staffing have been transferred to the universities in recent years, constraints remain in place as universities are part of the public sector financial and labour market regulations. For example, the number of management positions of pay grade 37 and above (E2, p 12) is limited, and determined by the Ministry of Finance. The cap on the number of professorships was abolished in 2008, but with respect to experienced professors (pay grade 38) the Ministry of Finance has set a maximum of 255 positions for the university sector as a whole. The appointment of a rector or prorector or any of the designated academic administrative positions, including deans and heads of departments, is subject to an externally fixed total number per university of such positions. With regard to staff remuneration, universities do have freedom in topping up the public-sector bargained minimum scale for employees in pay grades lower than 37 In addition, there are upper limits on salaries for the different leadership positions, from rector to heads of department, which must not be exceeded without the approval of the Ministry of Finance. As regards budgeting, while universities are free to draw up their own budgets, and to save and build up equity, they are not permitted to raise loans without prior authorisation from the Ministry of Finance [E2]. A majority of the Danish universities do not own their teaching and research facilities but rent them from the State, an issue that has been opened up for negotiations by the 2003 Act.

Funding arrangements, as well as development contracts, are important steering instruments available to the government. They can be tools for strategic steering, without resorting to direct operational intervention, or they can be used to limit university flexibility. Much depends on how they are shaped and implemented in practice.

Funding

The funding tracks for research in Denmark, as well as in comparable countries, are formed in several ways which influence the quality and effectiveness of research and promote research in fields especially important for the country. In the present funding system in Denmark, the direct funding consists of both free funding (the basic funding, also called the appropriation funding) and funding to fulfil the research-based public-sector services. The indirect funding track consists both of schemes which distribute funding on a competitive non-targeted basis with research quality as the main indicator and of schemes with pre-set targets for the research to be funded, in Danish often called “free schemes” and “strategic schemes” respectively.

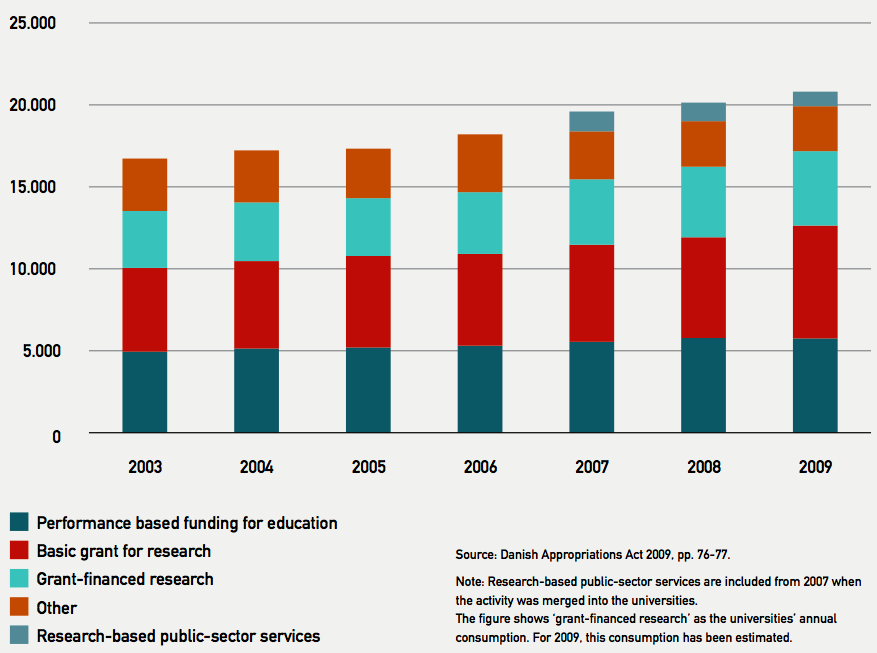

The universities must have sufficient basic funding for developing their research strategies and prioritisations as well as for financing high quality research-based education at PhD, master’s and bachelor’s levels. The basic funding component has increased considerably since 2003 (see figure 2 in annex 7), but the amount available by the competitive funding schemes have also increased, some schemes of which demand co-financing. The external “free funding”, received by individual researchers or research groups in competition especially from national and international funding councils, might also be used by the universities as a basis for prioritising top quality research activities which are, or in the longer term may develop into, knowledge areas of importance for society. This peer reviewed research may thus contribute to the (further) profiling of the university. Funding received from competitive “strategic schemes”, even though the research is restricted to certain fields, may also give the universities a framework for further strategic prioritisation decisions.

According to annex 7, table 4, the overall share of basic funding of the total funding for research has dropped from 64% (2003) to 56% (2009). Nonetheless, as mentioned, in absolute terms the amount of basic funding has increased during the later years, and the question whether the universities have sufficient room for deciding on strategic prioritisations of their own within the present financing conditions is not an easy one. It also depends on the extent to which basic funding is used for co-financing external funding. The Panel finds that the universities’ internal considerations for outlining an institutional strategy or profile, amongst other things, are dependent on the quality and competitiveness of their academic staff, and the effectiveness of the institutions’ personnel policies.

Development contracts

The development contracts [described in background document E7] could be used as individual, helpful tools for the universities’ strategic development and profiling, as well as for realising important targets, such as speeding up graduation and specific enrolment targets. However, we do not find the development contracts in their current practice effective enough as such steering instruments, as the explanatory notes to the University Act make them less appropriate for this role. The development contracts have become too detailed and process-oriented. In practice they consist of a list of indicators, on which universities provide data.

For an overview of the university sector, the Parliament, as well as the Ministry, obviously needs comprehensive information and statistics on the universities’ performance. This information is necessary and can be developed in dialogue with the universities, but it does not necessarily belong in a development contract.

Corrective action taken so far

Recognising the constraints placed on university flexibility, the Minister has initiated several committees and working groups to identify areas where university autonomy could be strengthened and where the rules do not correspond with requirements in the explanatory notes to the Draft Bill for the 2003 University Act. Many university-Ministry issues have been resolved through this mechanism and the Ministry is continuing to look into areas where regulation can be simplified or scrapped. At the time of the decision on the 2003 University Act, the political parties behind the Act listed ten degrees of freedom which should be sought established. Nine of these areas were implemented [E2, p 3]. The tenth, an increase in the maximum amount which can be earmarked for university construction without separate application to the Finance Committee, has been approved recently. However, it is the impression of the Panel that the universities do not see these degrees of freedom as the core of institutional autonomy. In 2007, the Minister appointed a committee which has come up with an additional ten areas where further de-regulation is being considered [E2, p 3]. Eight of these areas have reportedly been implemented in 2008 – 2009.

The development of university autonomy in the period after 2003 was dependent on the extent to which the universities have been able to use the opportunities offered by the University Act for becoming strategic actors and develop more direct and effective relationships with society, including the private sector and the international research community. As discussed in the previous sections, the Panel has observed that to some extent the universities have been hampered in the development of their strategic capacities by a dense set of government regulations. Nonetheless, this situation does not mean that the universities have been paralyzed and have had no room to manoeuvre at all.

Therefore, in this section, the Panel generally discusses how the universities have used the opportunities for autonomy offered by the 2003 University Act. Has the university sector as a whole become more strategic and diverse? Are there signs of differences between the universities with respect to the ways in which the 2003 University Act has been implemented?

The Panel has conducted its evaluation in the transition from what has been called the first generation university management to the second generation. The first generation of university managers has in many respects had to get used to the new responsibilities as well as opportunities offered by the University Act. At the same time, the university Boards have had to find their role in stimulating the strategic positioning of the universities. As indicated, the universities have been hampered by the Ministry and Parliament who have interfered in many ways in the details of the day-to-day operations of the universities. In addition, as will be discussed in following sections, overall the university managers have also had difficulties in finding the right balance between an executive leadership style and the need to involve staff and students in academic and administrative decision making processes.

University autonomy is not an aim in itself. In the Danish case, the reforms of the 2000s were expected, amongst other things, to lead to more intra-sector diversity through university profiling. There are a number of indications that suggest that the universities are becoming more strategically oriented and are taking the responsibilities seriously that have been transferred to them. A first indication consists of the strategic plans that most of the universities have produced. Even though there are differences between these plans when it comes to strategic focus and the clarity and consistency of the strategic goals included, they nonetheless show that the universities are in a process of becoming strategic actors. A second indication can be found in the careful attempts of a number of the universities to develop an explicit institutional profile, amongst other things, by using part of the basic funding to stimulate research programmes in areas where they have a strong track record. In addition, some universities have begun to proactively support researchers or research units in their applications to strategic research funds, e g. the ERC. The university Boards have played an important role in this. Overall, the Board members whom the Panel met during its visits in August 2009 have emphasized the importance of further strengthening the relationships of the universities to society in the coming period. Developing a clearer institutional profile was regarded as a core element in this.

Many countries around the world, e g. Australia, Finland, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, and the UK, are adapting their university governance approach in order to create the conditions under which their universities can compete at world class level. If the Danish university system is to become a genuine world class system, two basic governance conditions have to be fulfilled. Firstly, the Government and Parliament have to shift their university governance approach from detailed regulation to ‘steering at a distance’. Secondly, the universities have to become more proactive and focused in developing strategic priority areas and activities. Only the universities themselves are able to determine in which areas they can and want to compete at world-class level, even if external peer reviews are helpful for their decisions. In the abovementioned institutional strategic plans, confirmed in the Panel’s visits, the contours of these university priority areas carefully become visible. In most cases an important first step has been made, though a lot of work still needs to be done within the universities.

The first years after 2003 can be regarded as a learning period for all involved in university management in Denmark. The Panel points in this report to changes which are recommendable in the governance approach with respect to higher education. The recommended approach can be summarised as moving from detailed government regulation to ‘steering at a distance’, based on a high level of trust in the capacities of the universities to use the institutional autonomy in the expected way. Obviously, such a trust has to be ‘earned’ by the universities. They have to show that they are capable of operating as strategic actors. This can be regarded as one of the core challenges for the second generation university management in Denmark: The need to create the conditions and take the decisions that will allow their university to develop an appropriate institutional profile. This has to be in line with the university’s academic strengths, and make it possible for the university to participate in the global knowledge competition in such a way that it contributes to further strengthening the global competitiveness of the Danish economy.

In the Panel’s evaluation framework (chapter 3) a main issue is whether the 2003 University Act and other steering instruments following the Act, have influenced university autonomy and to what extent the universities operate as autonomous and accountable public institutions.

The Panel concludes that the universities have gained greater autonomy through the 2003 University Act and have become more dynamic because of the newly found autonomy. Notwithstanding these developments, there remain many constraints on university autonomy. In the Panel’s opinion, these are an expression by the Parliament, Government and ministries of low trust in the current capacity or willingness of the newly autonomous universities to deliver on national strategic goals set for them. Many regulations and dialoguebased demands placed on the universities go beyond their expected role as general steering strategies in pursuit of the politically set system-wide objectives. Instead they encroach on the university management prerogatives – they intrude on university decision-making regarding “how best to achieve” the overall targets of the political system.

→ Recommendations: Implementing a high-trust strategy

In the Panel’s opinion the way forward is to develop a high-trust strategy that stimulates the universities to deliver on mutually agreed missions by allowing them to operate in practice under higher levels of autonomy than is currently the case. The approach is to find less intrusive accountability mechanisms that would go hand in hand with new deregulations and would require changes on the part of the Parliament, the ministries as well as the universities.

To this end, the Panel offers the following two recommendations, which may require adjustment of the explanatory notes to the bill for the University Act:

> The Parliament and the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation should consider reviewing current regulations and reconsidering those that curtail universities’ freedom in their fields of competence.

The Panel recommends that the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation in collaboration with the universities actively examines all relevant regulations, including those from other Ministries, with a view to determine their continued use, or undertake actions for scrapping them or replacing them by other instruments. The decision should be based on the Minister’s task [as identified in the background document E2] as “formulating the framework for the universities’ activities; determining society’s requirements for the universities’ activities and the size of the subsidies from the Danish state to support these activities”. Regulations that infringe on the task of the universities to “safeguard the university’s interests as an educational and research institution and determine guidelines for its organisation, long term activities and development” should be removed. This may require an adjusted explanatory note to the University Act.

Thus a clear distinction should be drawn between what constitutes “strategic objectives” for the sector, the determination of which should be the province of the Parliament and the Ministry, and what constitutes “how to” achieve those objectives, which properly lies within the competence of the universities. Only those regulations that deal with setting the strategic objectives should be considered for retaining, while with respect to those regulations that deal with the areas where the universities can be expected to have the expertise and experience “to know best” removal should be considered.

Dialogue between the universities and the Ministry should be used to deal with system-wide objectives. The issue of reducing drop-out rates is an example: rather than the Parliament introducing a regulation for this purpose, it should engage in a dialogue with the universities to come to a decision concerning the actions the universities can take themselves. The taximeter system is a good example of a tool, which can be used to provide incentives for achieving system-wide goals.